Gallery: Complex Field Assignments

In the Aliases example, there were glossary entries that contained data about people, such as:\newglossaryentry{wellesley}{%

category={person},

name={Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington},

sort={Wellesley, Arthur},

first={Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington},

text={Wellesley},

description={Anglo-Irish soldier and statesman},

user1={1769-05-01},% born

user2={1852-09-14}% died

}

There’s a lot of repetition, which can get very tedious for a large number of similar entries.

The Aliases example deals with the post-description hook, which can be used to append the birth and death dates, so I’m going to omit the description, user1 and user2 fields for this example, and just consider an index of names rather than a glossary.

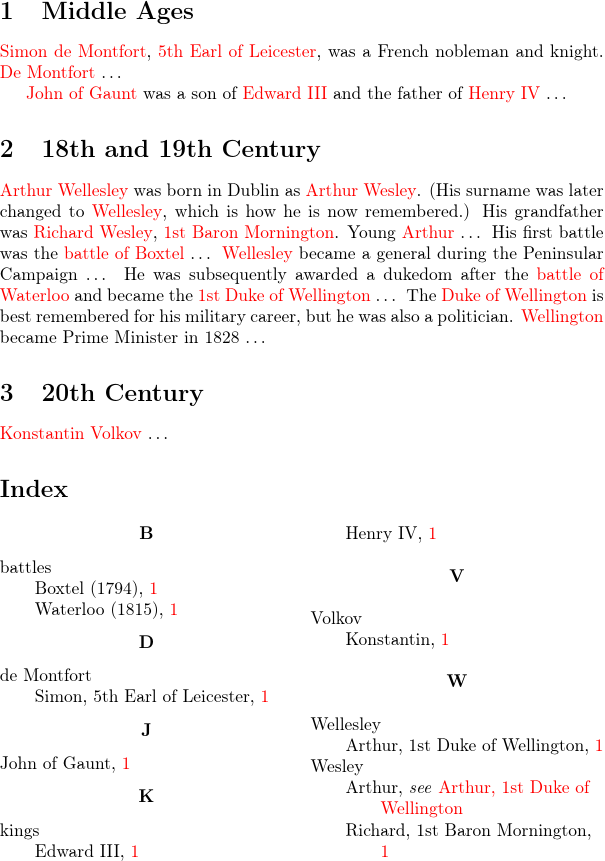

A non-fiction historical book that spans decades, or even centuries, may start out by referring to a person who acquired a rank during their lifetime by their real (or original) name (such as “Arthur Wellesley” or “Wellesley”). Later, the text may switch to referring to them by their formal title or designation (such as “the Duke of Wellington” or “Wellington”). For example:

\glsdisp{wellesley}{Arthur Wellesley} was born in Dublin.

Young \glsdisp{wellesley}{Arthur} …

% later

\glsdisp{wellesley}{Wellesley} became a general during

the Peninsular Campaign …

He was subsequently awarded a dukedom and became the

\glsdisp{wellesley}{1st Duke of Wellington} …

% later

The \glsdisp{wellesley}{Duke of Wellington} is best remembered

for his military career, but he was also a politician.

\glsdisp{wellesley}{Wellington} became Prime Minister in 1828 …

This is quite cumbersome to type. In this situation, \gls isn’t particularly useful as there are so many different ways to reference the person.

If your only concern is indexing and you have an entire section or chapter concerning the person, you could use an explicit range instead. For example:

\chapter{Arthur Wellesley (1st Duke of Wellington)}

\glsstartrange{wellesley}

Arthur Wellesley was born in Dublin.

Young Arthur …

% later

Wellesley became a general during

the Peninsular Campaign …

He was subsequently awarded a dukedom and became the

1st Duke of Wellington …

% later

The Duke of Wellington is best remembered

for his military career, but he was also a politician.

Wellington became Prime Minister in 1828 …

% end of chapter

\glsendrange{wellesley}

This is much easier to type, but is less useful if the chapter or section references multiple people rather than being a single block about one specific person.

Custom keys are useful in this case. For example:

\glsaddkey{forename}{}{\entryforename}{\Entryforename}{\forename}{\Forename}{\FORENAME}

\glsaddkey{surname}{}{\entrysurname}{\Entrysurname}{\surname}{\Surname}{\SURNAME}

\glsaddkey{rank}{}{\entryrank}{\Entryrank}{\rank}{\Rank}{\RANK}

\glsaddkey{formalprefix}{}{\entryformalprefix}{\Entryformalprefix}{\formalprefix}{\Formalprefix}{\FORMALPREFIX}

% place or territorial designation

\glsaddkey{place}{}{\entryplace}{\Entryplace}{\place}{\Place}{\PLACE}

% formal = rank + " of " + place

% OR formal = rank + " " + place

% OR formal = rank + " " + surname + " of " + place

% OR formal = rank + " " + surname

% OR …

\glsaddkey{formal}{}{\entryformal}{\Entryformal}{\formal}{\Formal}{\FORMAL}

% fullformal = formalprefix + " " + formal

\glsaddkey{fullformal}{}{\entryfullformal}{\Entryfullformal}{\fullformal}{\Fullformal}{\FULLFORMAL}

(This is a simplification, as not all names fit this format, and some people have multiple ranks or nicknames or diminutive forms. The example should be adapted as applicable.) Switching to bib2gls, the data is provide using @index in a bib file:

@index{wellesley,

name={Wellesley, Arthur, 1st Duke of Wellington},

text={Arthur Wellesley},

forename = {Arthur},

surname = {Wellesley},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Duke},

place = {Wellington},

formal = {Duke of Wellington},

fullformal = {1st Duke of Wellington}

}

Or if there are other Wellesleys, a hierarchical structure may be more applicable:

@index{Wellesley}

@index{Arthur-Wellesley,

parent={Wellesley},

name={Arthur, 1st Duke of Wellington},

text={Arthur Wellesley},

forename = {Arthur},

surname = {Wellesley},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Duke},

place = {Wellington},

formal = {Duke of Wellington},

fullformal = {1st Duke of Wellington}

}

In both cases, there’s a lot of repetition. I’m assuming the second case, where the index is large with multiple entries with the same surname. Let’s suppose the index also contains other types of entries, such as battles. What I’m aiming for is a much simpler bib file that eliminates duplication as much as possible. The custom entry types (@person, @monarch and @battle) will all be aliased to @index. (Remember that labels can’t contain spaces, so I’ve used hyphens.)

@index{Wellesley}

@person{Arthur-Wellesley,

parent={Wellesley},

forename = {Arthur},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Duke},

place = {Wellington}

}

@index{Wesley}

@person{Richard-Wesley,

parent={Wesley},

forename = {Richard},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Baron},

place = {Mornington}

}

@person{Arthur-Wesley,

parent={Wesley},

forename={Arthur},

alias={Arthur-Wellesley}

}

@index{de-Montfort, name={de Montfort}}

@person{Simon-de-Montfort,

parent={de-Montfort},

forename={Simon},

formalprefix={5th},

rank={Earl},

place={Leicester}

}

@index{Volkov}

@person{Konstantin-Volkov,

parent = {Volkov},

forename = {Konstantin}

}

@person{John-of-Gaunt,

forename={John},

place={Gaunt}

}

@indexplural{king}

@monarch{Henry-IV,

parent={king},

forename={Henry},

ordinal={IV}

}

@monarch{Edward-III,

parent={king},

forename={Edward},

ordinal={III}

}

@indexplural{battle}

@battle{Battle-of-Waterloo,

parent={battle},

place={Waterloo},

date={1815}

}

@battle{Battle-of-Boxtel,

parent={battle},

place={Boxtel},

date={1794}

}

This requires extra custom keys ordinal and date but these can be simple storage fields:

\glsaddstoragekey{ordinal}{}{\entryordinal}

\glsaddstoragekey{date}{}{\entrydate}

The example text is now:

\section{Middle Ages}

\gls{Simon-de-Montfort}, \fullformal{Simon-de-Montfort}, was a French nobleman and knight.

\Surname{Simon-de-Montfort} …

% later

\gls{John-of-Gaunt} was a son of \gls{Edward-III} and the father of \gls{Henry-IV} …

% much later

\section{18th and 19th Century}

\gls{Arthur-Wellesley} was born in Dublin as \gls{Arthur-Wesley}.

(His surname was later changed to \surname{Arthur-Wellesley}, which is how

he is now remembered.) His grandfather was \gls{Richard-Wesley}, \fullformal{Richard-Wesley}.

Young \forename{Arthur-Wellesley} …

% later

His first battle was the \gls{Battle-of-Boxtel} …

% later

\surname{Arthur-Wellesley} became a general during

the Peninsular Campaign …

He was subsequently awarded a dukedom after the \gls{Battle-of-Waterloo} and became the

\fullformal{Arthur-Wellesley} …

% later

The \formal{Arthur-Wellesley} is best remembered

for his military career, but he was also a politician.

\place{Arthur-Wellesley} became Prime Minister in 1828 …

\section{20th Century}

\gls{Konstantin-Volkov} …

Whether or not you prefer this to the original is a matter of personal preference. With \glsdisp, you can at least see what the text is as you edit the source code, but the custom keys can make it more compact and improve consistency in formatting.

The object of this exercise is to make the contents of the bib file equivalent to:

@index{Wellesley}

@index{Arthur-Wellesley,

parent={Wellesley},

name={Arthur, 1st Duke of Wellington},

text={Arthur Wellesley},

forename = {Arthur},

surname = {Wellesley},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Duke},

place = {Wellington},

formal = {Duke of Wellington},

fullforml = {1st Duke of Wellington}

}

@index{Wesley}

@index{Richard-Wesley,

parent={Wesley},

name={Richard, 1st Baron Mornington},

text={Richard Wesley},

forename = {Richard},

surname = {Wesley},

formalprefix = {1st},

rank = {Baron},

place = {Mornington},

formal={Baron Mornington},

fullformal = {1st Baron Mornington}

}

@index{Arthur-Wesley,

parent={Wesley},

name={Arthur},

text={Arthur Wesley},

forename={Arthur},

surname = {Wesley},

alias={Arthur-Wellesley}

}

@index{de-Montfort, name={de Montfort}}

@index{Simon-de-Montfort,

parent={de-Montfort},

name={Simon, 5th Earl of Leicester}

forename={Simon},

surname={de Montfort},

formalprefix={5th},

rank={Earl},

place={Leicester},

formal={Earl of Leicester},

fullformal={5th Earl of Leicester}

}

@index{Volkov}

@index{Konstantin-Volkov,

parent = {Volkov},

name = {Konstantin},

surname = {Volkov},

forename = {Konstantin},

text = {Konstantin Volkov}

}

@index{John-of-Gaunt,

name={John of Gaunt},

forename={John},

place={Gaunt}

}

@indexplural{king}

@index{Henry-IV,

parent={king},

name={Henry~IV},

forename={Henry},

ordinal={IV}

}

@index{Edward-III,

parent={king},

name={Edward~III},

forename={Edward},

ordinal={III}

}

@indexplural{battle}

@index{Battle-of-Waterloo,

parent={battle},

name={Waterloo},

text={Battle of Waterloo},

place={Waterloo},

date={1815}

}

@index{Battle-of-Boxtel,

parent={battle},

name={Boxtel (1794)},

text={Battle of Boxtel},

place={Boxtel},

date={1794}

}

The basename of the bib file has the same name as the basename of the LaTeX source file (\jobname) so I can omit the src resource option. Converting @person, @monarch and @battle to @index is fairly straight-forward:

\GlsXtrLoadResources[

entry-type-aliases={

person=index,

monarch=index,

battle=index

}

]

The difficult part is filling in the missing fields. Let’s first consider the replicate-fields resource option. This has the syntax:

replicate-fields={

src-field = {dest-field1, dest-field2, …},

…

src-field = {dest-field1, dest-field2, …}

}

On the left is the name of the source field (src-field) and on the right is a list of destination fields. The value of the source field is copied into each of the destination fields (if the field hasn’t already been set). For example:

replicate-fields={

forename={name,first,text},

parent={surname}

}

This copies the value of the forename field into the name, first and text fields, and copies the value of the parent field (which contains a label) to the surname field. This would make, for example, the Simon-de-Montfort entry equivalent to:

@index{Simon-de-Montfort,

parent={de-Montfort},

surname={de-Montfort},

forename={Simon},

name={Simon},

first={Simon},

text={Simon},

formalprefix={5th},

rank={Earl},

place={Leicester}

}

This isn’t the desired result. The surname should actually correspond to the parent’s name field (not the label), the first and text fields (used by \gls) don’t include the surname and the name field doesn’t include the formal title. It also doesn’t address the requirements for the monarch or battle entries, and would lead to “king” as the surname for the Henry-IV entry and “battle” as the surname for the battle entries.

The assign-fields option has different (and much more complex) syntax. As with replicate-fields, the value is a comma-separated list of assignments, but each assignment has the syntax:

dest-field =[override] element-list [condition]Note that the destination field is now on the left (whereas with

replicate-fields the destinations are in a comma-separate list on the right).

The optional parts in square brackets may be omitted. The override option (if present), should either be o (override) or n (no override). This indicates whether or not the field assignment should take place if the destination field (dest-field) has already been set. The default is no override, which means that if the destination field has been set, the assignment will be skipped.

The final optional part condition is a conditional statement. If the condition evaluates to true, the assignment will be applied (unless the override setting forbids it) otherwise the assignment is skipped.

With no override on, this means that you can have multiple assignments for the same field, which means that if an assignment is skipped (for example, if the condition evaluates to false), another attempt may be made. Once the field has been set, subsequent statements for that field will automatically be skipped.

The element-list part is a string concatenation expression. If any element within the list evaluates to null, the entire assignment is skipped. (This action can be changed, see the manual.)

You may be familiar with string concatenation in bib files. For example, if you have used BibTeX, you may have done something like:

@string{JOHNSMITH = {John Smith}}

@string{JANEDOE = {Jane Doe}}

@article{smith2023,

author = JOHNSMITH # { and } # JANEDOE,

title = {An interesting paper},

journal = {etc}

}

@article{doe2023,

author = JANEDOE # " and " # JOHNSMITH,

title = {Another interesting paper},

journal = {etc}

}

This is an example of bib string concatenation. Literal strings are delimited by braces { and } or double quotes " and ". Content that isn’t delimited (such as JOHNSMITH and JANEDOE, in the above example) is a reference, and the actual string value needs to be looked up. The concatenation operator is the hash # symbol.

The string concatenation syntax for certain resource options, such as assign-fields, is similar, but the concatenation operator is the plus + symbol (# is a special character in tex files and too awkward to supply in a resource option). Literal strings must also be delimited, in the same way as in bib files, either with braces or double-quotes.

The references are somewhat different as, instead of referencing a @string variable, they are now referencing a field value. It’s also possible to use a bib2gls quark (not the same as a LaTeX3 quark), which is a special token that looks like a LaTeX command but is actually an instruction to bib2gls to perform some function. If you want to use any of these quarks, you must add the following to your preamble (before \GlsXtrLoadResources):

\renewcommand*{\glsxtrresourceinit}{%

\GlsXtrResourceInitEscSequences

}

(The alternative is to prefix every quark with \string which can be quite tiresome.) You will need glossaries-extra v1.51+ for the above. The above block of code locally redefines the quark commands to expand to their literal control sequence name while the resource options are being written to the aux file. For example, \NULL will expand to \string\NULL\space within the context of \GlsXtrLoadResources, but outside of resource options it won’t be defined (unless it also happens to be defined by another package or is a custom user command). Note that \GlsXtrResourceInitEscSequences isn’t automatically added to the definition of \glsxtrresourceinit because there is the potential for conflict and the quarks are only required for a small set of advanced resource options.

The full syntax is described in the bib2gls user manual. The information here is simplified. A field reference is essentially in the form

entry-ref -> field-refwhere entry-ref is one of:

self (the entry having its dest-field field modified), parent (the parent entry, as identified by the label given in the parent field) or root (the hierarchical root).

So, for example,

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name

}

means that the surname field is set to the name field from the parent entry. Note that this is different from the earlier

replicate-fields={

parent={surname}

}

which sets the surname field to the value of the parent field (which is the label identifying the parent entry).

The following example, sets the surname as previously and then the text field to the value of the forename field concatenated with a space and the value of the surname field:

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name,

text = self -> forename + { } + self -> surname

}

The first assignment sets the surname, which means that the surname is then available for the second assignment. The “self -> ” part is optional as long as it’s not ambiguous, so this can be written more simply as:

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name,

text = forename + { } + surname

}

Any error messages regarding the syntax of assign-fields will typically fill in the missing “self -> ” to clarify how the assignment rule has been interpreted.

It’s easy to make a mistake in the assign-fields syntax, especially if you have many assignments, but it’s also hard for bib2gls to direct you to the location of the error. Remember that bib2gls picks up the information from the aux file and does not read the tex file. This means that it’s unable to provide a line number. It’s therefore best to try out each assignment by building the document after each addition. If you try to type in all assignments in one go and then build the document, you may find it hard to discover a syntax error.

For the entries without a parent, the reference parent -> name will resolve to null, which means that the assignment will be skipped. This means that the John-of-Gaunt entry won’t have the surname field set. This means that the second assignment, which tries to set the text field, will also fail because the surname field reference evaluates to null.

Unfortunately, the above rules set the surname field to “kings” for the Henry-IV entry and the text field to “Henry kings”, which is incorrect. Similarly, the battle entries (for which a surname makes no sense), have the surname field set to “battles”. This is where the conditional is required. These rules should only apply to the entries that were defined with the custom @person entry type.

In addition to referencing a field belonging to the entry or one of its ancestors, it’s also possible to reference the entry type, label, or bib file that the entry was defined in. The syntax is:

label-type -> label-delineatorwhere label-type may be one of:

entrytype (the entry type without the leading @), entrylabel (the entry label) or entrybib (the bib file). The label-delineator may be one of: original or actual. The meaning of the delineator varies according to label-type (see the manual), but for this example, we’re interested in the original entry type, which can be referenced with

entrytype -> originalA conditional can now be added to the first assignment that will only set the

surname field to the value of the name field of the parent entry, for entries that were defined using the custom @person:

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name [ entrytype -> original = "person"],

text = forename + { } + surname

}

This won’t set the surname field for the John-of-Gaunt entry because it doesn’t have a parent, and won’t set the surname field for the Henry-IV or the battle entries because they weren’t defined with @person. If the surname field isn’t set, then the second assignment will be skipped because it has one or more elements that evaluate to null.

The following deals with the text field for all cases in the example:

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name [ entrytype -> original = "person" ],

text = {battle of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "battle" ],

text = forename + { } + surname,

text = forename + { of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "person" ],

text = forename + {~} + ordinal [ entrytype -> original = "monarch" ],

text = forename

}

Note that there are five assignment rules for the text field. The first one that satisfies the condition (where one is provided) or that has all referenced values evaluating to non-null is the rule that will be applied. The remaining rules will be skipped, because the field has now been set.

The fullformal field is easy to set. The first attempt will combine the formalprefix field with the formal field. If that fails then fullformal can simply be set to formal:

fullformal = formalprefix + { } + formal,

fullformal = formal

However, the formal field will first need to be set. This is quite complicated. For the Duke of Wellington and the Earl of Leicester the rule is rank + { of } + place but for Baron Mornington the rule is rank + { } + place. So far, the example has used string equality tests (such as entrytype -> original = "person"). It’s also possible to test a regular expression:

formal = rank + { of } + place [ rank = /Duke|Earl/ ],

(Note that the regular expression is anchored, which means this is equivalent to /^Duke|Earl$/ but avoids awkward special characters in the resource option.) In this case, I don’t need to test the entry type as the battle entries don’t have the rank field set.

Again, multiple assignment rules may be provided:

formal = rank + { } + place [ rank = /Baron|Viscount/ ],

formal = rank + { } + surname

Other names may have rules like rank + { } + surname + { of } + place. The example can be adapted as applicable. If an entry has a formal name that doesn’t fit the provided rules, then the formal field will have to be explicitly set in the bib file.

The name field is also complicated. Let’s start with the John-of-Gaunt entry, which has original entry type @person and no parent field. This means that the parent field is null. Remember that the “self ->” part can be omitted, so parent on its own (that is, not followed by ->) means self -> parent, which is the current entry’s parent field.

You can test for null using the \NULL quark. Remember from earlier that quarks aren’t LaTeX commands and need to be protected from expansion whilst they are written to the aux file.

So, to set the name field to “John of Gaunt”:

name = forename + { of } + place

[ entrytype -> original = "person" & parent = \NULL]

This has two conditions joined with an “and” boolean operator (&), so both conditions have to be true: the original entry type must be “person” and the parent field must be null (not set).

The rules for the other entries are as follows:

name = forename + {, } + fullformal

[ entrytype -> original = "person"],

name = forename + {~} + ordinal,

name = forename,

name = place + { (} + date + {)} [ entrytype -> original = "battle"],

name = place [ entrytype -> original = "battle"]

The complete document code follows. (The initial comment lines below are arara directives. You can

remove them if you don’t use arara.)

% arara: pdflatex

% arara: bib2gls: { group: on }

% arara: pdflatex

% arara: pdflatex

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[T1]{fontenc}

\usepackage[colorlinks]{hyperref}

\usepackage[record,stylemods={bookindex}]{glossaries-extra}

\glsaddkey{forename}{}{\entryforename}{\Entryforename}{\forename}{\Forename}{\FORENAME}

\glsaddkey{surname}{}{\entrysurname}{\Entrysurname}{\surname}{\Surname}{\SURNAME}

\glsaddkey{rank}{}{\entryrank}{\Entryrank}{\rank}{\Rank}{\RANK}

\glsaddkey{formalprefix}{}{\entryformalprefix}{\Entryformalprefix}{\formalprefix}{\Formalprefix}{\FORMALPREFIX}

% place name or territorial designation

\glsaddkey{place}{}{\entryplace}{\Entryplace}{\place}{\Place}{\PLACE}

% rank + " of " + place

\glsaddkey{formal}{}{\entryformal}{\Entryformal}{\formal}{\Formal}{\FORMAL}

% formalprefix + formal

\glsaddkey{fullformal}{}{\entryfullformal}{\Entryfullformal}{\fullformal}{\Fullformal}{\FULLFORMAL}

\glsaddstoragekey{ordinal}{}{\entryordinal}

\glsaddstoragekey{date}{}{\entrydate}

\renewcommand*{\glsxtrresourceinit}{%

% Requires glossaries-extra v1.51:

\GlsXtrResourceInitEscSequences

}

\GlsXtrLoadResources[

entry-type-aliases={

person=index,

monarch=index,

battle=index

},

assign-fields={

surname = parent -> name [ entrytype -> original = "person"],

text = {battle of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "battle"],

text = forename + { } + surname,

text = forename + { of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "person"],

text = forename + {~} + ordinal [ entrytype -> original = "monarch"],

text = forename,

formal = rank + { of } + place [ rank = /Duke|Earl/ ],

formal = rank + { } + place [ rank = /Baron|Viscount/ ],

formal = rank + { } + surname,

fullformal = formalprefix + { } + formal,

fullformal = formal,

name = forename + { of } + place

[ entrytype -> original = "person" & parent = \NULL],

name = forename + {, } + fullformal

[ entrytype -> original = "person"],

name = forename + {~} + ordinal,

name = forename,

name = place + { (} + date + {)} [ entrytype -> original = "battle"],

name = place [ entrytype -> original = "battle"]

}

]

\begin{document}

\section{Middle Ages}

\gls{Simon-de-Montfort}, \fullformal{Simon-de-Montfort}, was a French nobleman and knight.

\Surname{Simon-de-Montfort} …

% later

\gls{John-of-Gaunt} was a son of \gls{Edward-III} and the father of \gls{Henry-IV} …

% much later

\section{18th and 19th Century}

\gls{Arthur-Wellesley} was born in Dublin as \gls{Arthur-Wesley}.

(His surname was later changed to \surname{Arthur-Wellesley}, which is how

he is now remembered.) His grandfather was \gls{Richard-Wesley}, \fullformal{Richard-Wesley}.

Young \forename{Arthur-Wellesley} …

% later

His first battle was the \gls{Battle-of-Boxtel} …

% later

\surname{Arthur-Wellesley} became a general during

the Peninsular Campaign …

He was subsequently awarded a dukedom after the \gls{Battle-of-Waterloo} and became the

\fullformal{Arthur-Wellesley} …

% later

The \formal{Arthur-Wellesley} is best remembered

for his military career, but he was also a politician.

\place{Arthur-Wellesley} became Prime Minister in 1828 …

\section{20th Century}

\gls{Konstantin-Volkov} …

\printunsrtglossary[title={Index},style={bookindex}]

\end{document}

If you don’t use arara, you need to run the following commands:

pdflatex assign-fields

(See Incorporating makeglossaries or makeglossaries-lite or bib2gls into the document build.)

Download: PDF (58.27K), source code (3.24K), assign-fields.bib (1.23K).

Extras

If you want “Battle of …” instead of “battle of …” in the text, either use \Gls instead of \gls or adjust the case in the rule:

text = {Battle of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "battle" ]

If you are likely to need a plural (for example, if multiple battles occurred in the same place), then remember to add a rule for the plural key. For example:

plural = {battles of } + place [ entrytype -> original = "battle" ]

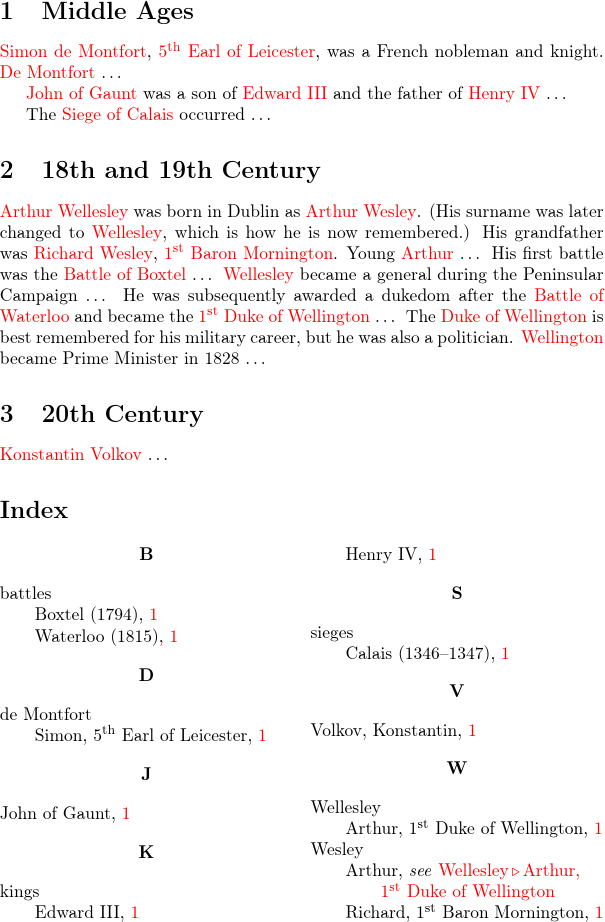

If you also have sieges, conquests, invasions etc, you can use something similar, but it may be that you don’t want a separate rule for each. For example,

@indexplural{siege}

@battle{Siege-of-Calais-1346,

parent={siege},

place={Calais},

date = {1346--1347}

}

The assignment now needs to be adjusted so that it can fetch the appropriate word from the parent entry:

text = parent -> text + { of } + place

[ entrytype -> original = "battle" ],

plural = parent -> plural + { of } + place

[ entrytype -> original = "battle" ]

If you want to change the case, you can use one of the case-changing quarks:

text = \FIRSTUC { parent -> text } + { of } + place

[ entrytype -> original = "battle"]

Sometimes you may find that you only have a single sub-entry. For example, you may only have one person indexed with a particular surname. You may want to flatten this entry (remove its hierarchy), particularly if you have a large book with a large index and you need to compress it where possible. Entries can be flattened with the flatten-lonely rule. For example:

flatten-lonely=postsort,However, if the sub-entry has a particularly long name (such as in Wellington’s case), this may not lead to any space saving and can look cluttered. In which case, you may want to only conditionally flatten the sub-entry, depending on the combined length of the parent name and child name. This can be done with the

flatten-lonely-condition option, which has the same syntax as the condition part of assign-fields. For example:

flatten-lonely-condition={

\LEN{ parent -> name + name } < 25 & entrytype -> original = "person"}

This uses another quark \LEN which will return the number of characters in the string expression in its argument. This will remove the hierarchy from the Konstantin-Volkov entry, but not from the Arthur-Wellesley entry (because the combined parent -> name + name length is greater than 25 and not from the Siege-of-Calais-1346 entry (because the original entry type wasn’t @person).

Note that \LEN detokenizes the resulting string, so the character count includes the number of characters in detokenized control sequence names.

For example, if the formalprefix field is set to 1\textsuperscript{st} then \LEN{formalprefix} will return 21. If you want to strip commands, then interpret the value first:

flatten-lonely-condition={

\LEN{ \INTERPRET { parent -> name + name } } < 25 & entrytype -> original = "person"}

Perhaps you have now decided that you want to encapsulate the suffix part of the ordinals in the formalprefix fields, to make it easier to customize. For example, 1\ordsuffix{st}, where \ordsuffix is a custom command that can be modified to suit requirements.

This could be done by altering the bib file. For example:

@preamble{"\providecommand{\ordsuffix}[1]{#1}"}

@index{Wellesley}

@person{Arthur-Wellesley,

parent={Wellesley},

forename = {Arthur},

formalprefix = {1\ordsuffix{st}},

rank = {Duke},

place = {Wellington}

}

However, you may prefer not to edit the bib file. The substitutions can instead be made with an extra assign-fields rule (which needs to be inserted before any reference to the formalprefix field):

formalprefix =[o] \MGP{1} + "\cs{ordsuffix}{" + \MGP{2} + "}"

[ formalprefix = /(\cs{d}+)(st|nd|rd|th)/ ]

Note that I’ve used the override setting. This is required if you want to modify a field that has already been set. Note also that unmatched braces in literal strings must use the double-quote delimiter rather than brace delimiters.

The \MGP quark is used when the condition is a regular expression match and can be used to reference a captured group. The \cs{csname} command is locally defined by \GlsXtrResourceInitEscSequences to expand to the detokenized control sequence name \csname as it’s written to the aux file. So \cs{ordsuffix} is written to the aux file as the literal string \ordsuffix, which is then parsed by bib2gls as the LaTeX command \ordsuffix (which it won’t recognised unless it’s provided in the @preamble). Similarly, \cs{d} is written to the aux file as the literal string \d, so the condition is parsed by bib2gls as formalprefix = /(\d+)(st|nd|rd|th)/. In this case, \d occurs in a regular expression so it represents a digit.

If the formalprefix field is set to 1st, then it matches the regular expression. The first group, referenced by \MGP{1}, is 1 and the second group, referenced by \MGP{2}, is st. So the field value is set to 1\ordsuffix{st}. Remember that \ordsuffix will need to be defined in the document.

Finally, the cross-reference resulting from the alias field in the Arthur-Wesley entry doesn’t include the surname (parent entry name). This can be achieved by redefining \glsseeitemformat to use \glsxtrhiername.

Download: PDF (82.01K), source code (3.79K).